As part of my research into the formal qualities of Paranormal Romance, and how different genres encounter each other to generate this new kind of novel, I’m immersing myself into one of its forbears. Gothic Romance (sometimes known as fantasy romance or romantic suspense) has affinities with Jane Eyre (1847) and Wuthering Heights (1847) and is perhaps epitomised by Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938). Subsequent writers such as Mary Stewart, Victoria Holt, Barbara Michaels, and Madeleine Brent proliferated from the 1950s to the 1970s.

As part of my research into the formal qualities of Paranormal Romance, and how different genres encounter each other to generate this new kind of novel, I’m immersing myself into one of its forbears. Gothic Romance (sometimes known as fantasy romance or romantic suspense) has affinities with Jane Eyre (1847) and Wuthering Heights (1847) and is perhaps epitomised by Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938). Subsequent writers such as Mary Stewart, Victoria Holt, Barbara Michaels, and Madeleine Brent proliferated from the 1950s to the 1970s.

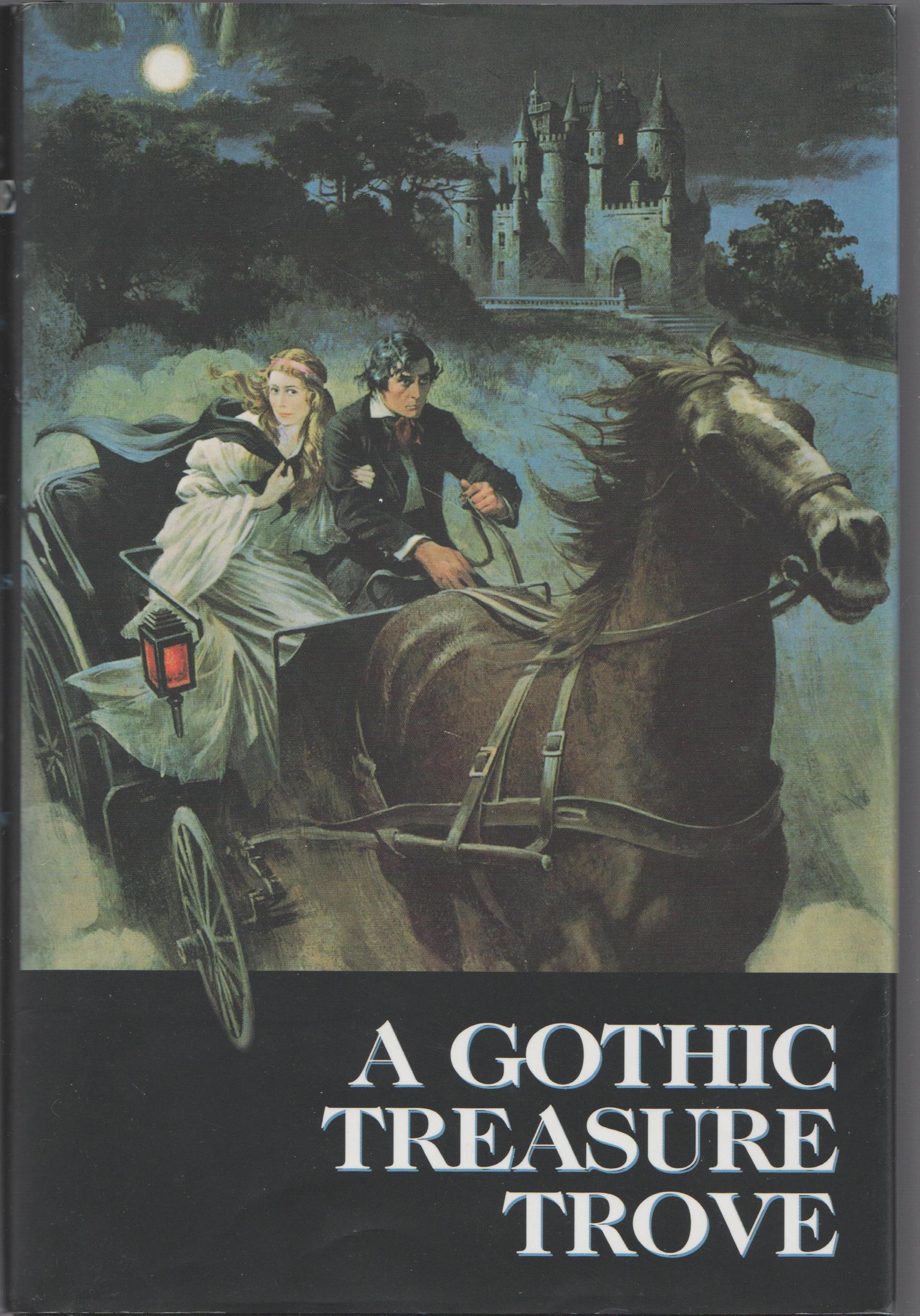

These novels rarely embrace the supernatural; it may be suggested but it is usually resolved in the manner of Ann Radcliffe’s novels. But key motifs of moonlight, darkness, and shadows; subterranean passages and caverns abound. The protagonists are endangered, vulnerable (though often plucky) young women—orphans, governesses, or companions. The hero will be brooding and have dark secrets. There may be indecision by the heroine in her choice of love object between two men, one who seems more benign than the other (but appearances are often deceptive). Often an antiquated family home is central; abbeys or castles may appear. The covers of these novels are highly atmospheric and portray those Gothic themes; likewise, the gloriously kitschy illustrations in the Reader’s Digest anthology I found, A Gothic Treasure Trove (2001).

This collection is laden with paratextual markings of the Gothic, from the cover (above) and the illustrations below to the blurb on the back of the dust jacket, which characterises the anthologised works as ‘A Gothic novel which fulfils the old traditions of brooding atmosphere, suspense and romance’, ‘remains taut as it moves from castle to cave to scaffold and from disaster to deception’, and ‘suspenseful and bewitching’.

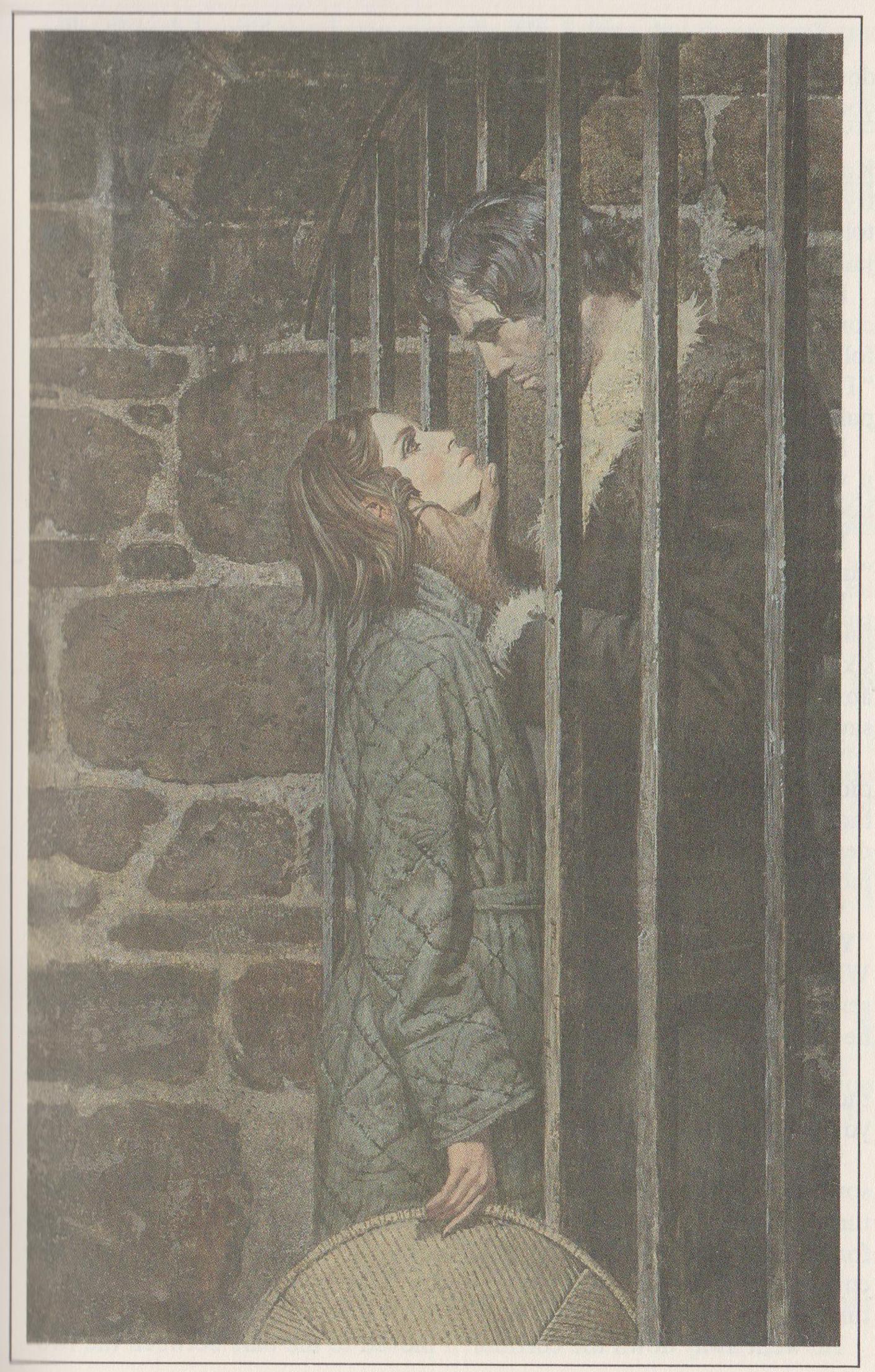

Incarceration is a common theme in the original Gothic; Madeleine Brent’s heroine Lucy meets her lover while both are imprisoned in the exciting adventure of Moonraker’s Bride (1973). Lucy is particularly unconventional, resourceful, and courageous (which may not be surprising to those who know the Modesty Blaise spy stories by Peter O’Donnell, who also wrote as ‘Madeleine Brent’).

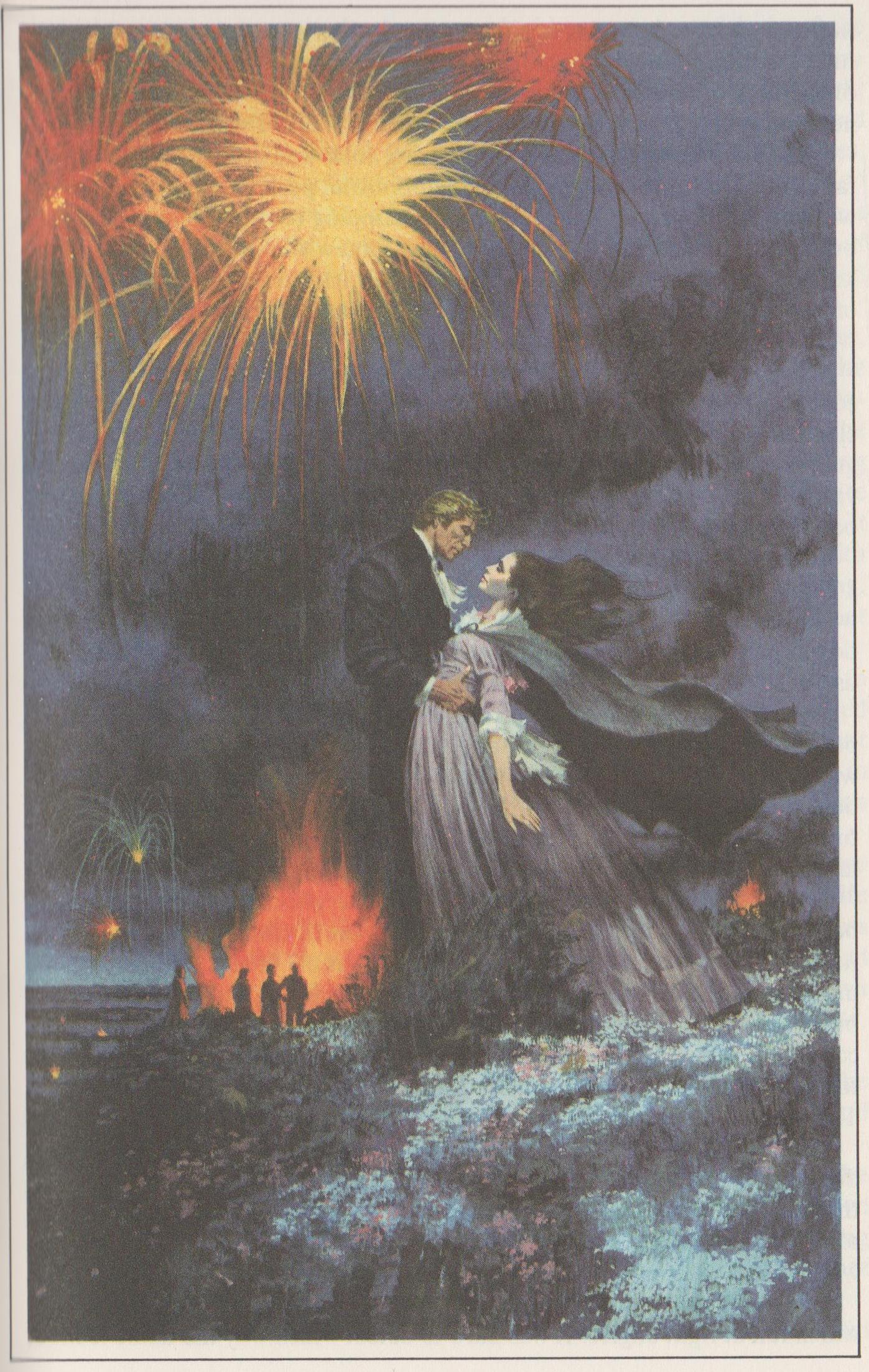

Lucy has an explosive first kiss at a fireworks party:

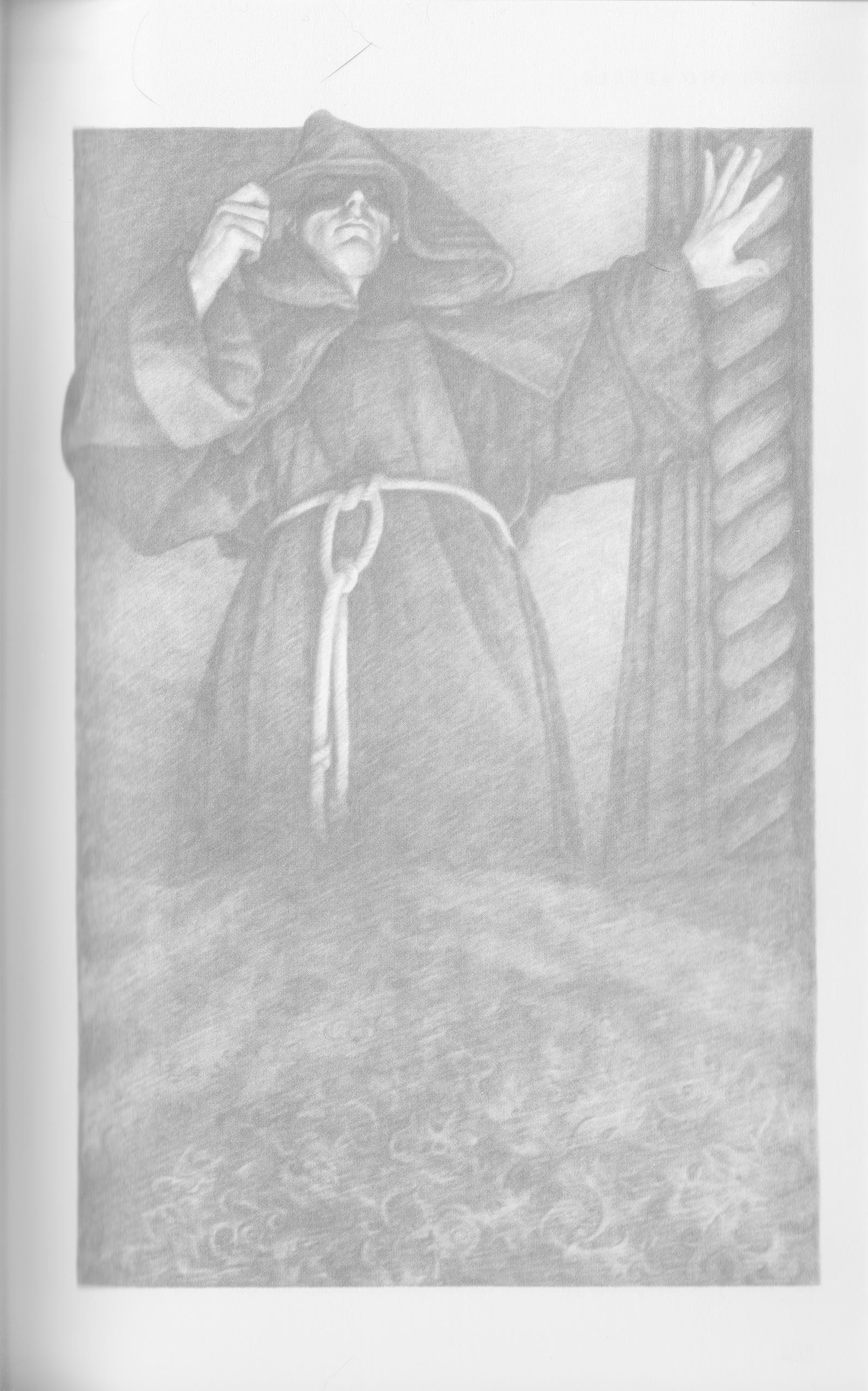

Any Gothic heroine worth her salt must encounter a creepy monk at some point in her career; Catherine, in Victoria Holt’s Kirkland Revels (1962), is nearly sent to the madhouse because of this one:

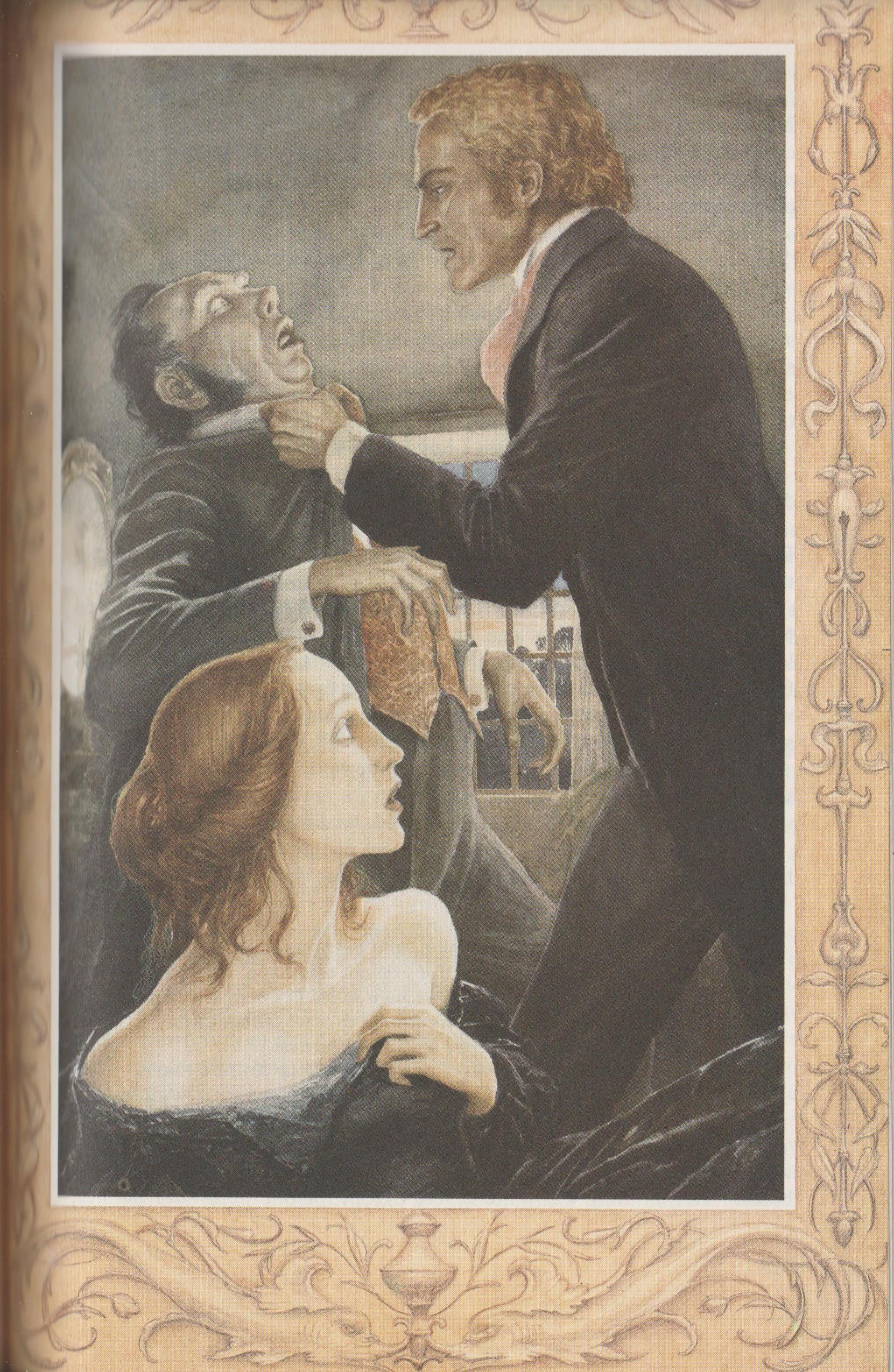

And men must fight to protect their womenfolk, as in Barbara Michaels’s Wings of the Falcon (1977):

And men must fight to protect their womenfolk, as in Barbara Michaels’s Wings of the Falcon (1977):

Mary Stewart, in Thunder on the Right (1957), deliberately invokes Ann Radcliffe, acknowledging her Gothic origins. Here, the heroine visits a convent in France in quest of her vanished friend: and encounters a young door-keeper:

But her eyes, still staring as if fascinated, held in them some uneasiness that Jennifer by no means liked. Under that childish china-blue brightness it was as if dismay lurked—yes, and some obscure horror. Something, at any rate, that was not just mere shyness and fear of strangers; something that was beginning to communicate itself to Jennifer in the faintest premonitory prickling of the spine. Something, Jennifer told herself sharply, that was being dragged up out of the depths of the subconscious, where half a hundred romantic tales had contributed to feed the secular mind with a superstitious fear of the enclosing convent walls. This, she added with some asperity, as she stepped past the staring orphan into a tiny courtyard, was not a story in the Radcliffe vein, where monastic cells and midnight terrors followed one another as the night the day, this was not a Transylvanian gorge in the dead hour of darkness. It was a small and peaceful institution, run on medieval lines perhaps, but nevertheless basking in the warm sunshine of a civilized afternoon. (26)

Yet this deflation of Radcliffe is a narrative ploy, of course, as the discerning reader will know, and ironises the heroine’s innocence of what will follow. And note Stewart’s Radcliffean use of Continental Europe as otherness, including a Catholicism that is in opposition to Enlightened progress, is still potent.

I must admit I’m enjoying these novels enormously. They’re well-crafted, with gripping plots and often engaging characters. Among other things, they capture well the intensity of first love and the utopianism of mutuality between the sexes that is found in YA paranormal romance. They are not as ideologically regressive as one might expect. Stewart’s novels in particular explore ideas of masculinity and heroism, and have a distinctly feminist strand of female autonomy together with a critique of masculinist values. I’ll be presenting some of this research at the forthcoming IGA Conference.

Photo by

Photo by  Then, there is Le Guin’s famous Earthsea series (originally a trilogy) for young adults. This illustrates vividly her sense of the variety of human culture, with its tales of wizards and dragons traversing the diverse islands of the vast archipelago that is Earthsea. There is a profound concern with the relationship of language to reality, explored through the apparatus of casting spells. Again, the depth of her characters and the attention she pays to their development is to be celebrated.

Then, there is Le Guin’s famous Earthsea series (originally a trilogy) for young adults. This illustrates vividly her sense of the variety of human culture, with its tales of wizards and dragons traversing the diverse islands of the vast archipelago that is Earthsea. There is a profound concern with the relationship of language to reality, explored through the apparatus of casting spells. Again, the depth of her characters and the attention she pays to their development is to be celebrated.

I’ve not seen Guillermo del Toro’s film The Shape of Water yet, but it appears to be an intriguing take on the ‘Beauty and the Beast’ archetype that lies behind the genre of Paranormal Romance. With its love affair between human woman and fabulous aquatic being it also, of course, resonates with the myths and legends of

I’ve not seen Guillermo del Toro’s film The Shape of Water yet, but it appears to be an intriguing take on the ‘Beauty and the Beast’ archetype that lies behind the genre of Paranormal Romance. With its love affair between human woman and fabulous aquatic being it also, of course, resonates with the myths and legends of