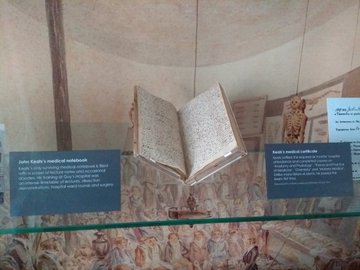

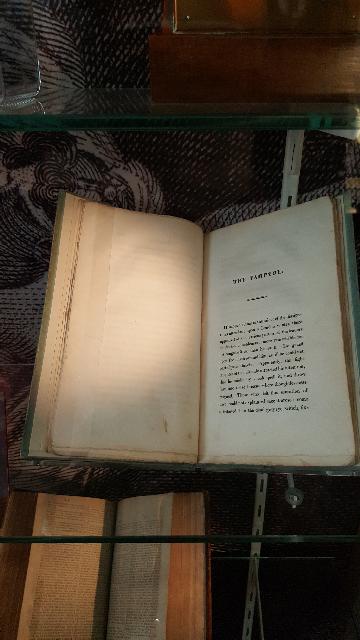

This event was not only the bicentenary of the publication of ‘The Vampyre’ but also 200 years since John Keats lived at the conference venue: the beautiful Keats House, Hampstead. We began the symposium with a fascinating tour round the house by Rob Shakespeare where we saw a first edition of ‘The Vampyre’ (which may possibly have been owned by Keats).

Our first paper was by Nick Groom, who began with an outline of the reports on vampires from Eastern Europe that arose in the early eighteenth century and how they were transformed into literary form. Referring to the momentous occasion in 1816 at the Villa Diodati, Nick elaborated an unexpected and illuminating notion of the vampiric elements in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (Mary, we learn, had called Percy a vampire), such as blood imagery, blood transfusion, and the story itself as contagious and blood-chilling. This culminates in a reading of Frankenstein as recognising the situation of non-human nature.

Ivan Phillips then explored the centrality of the gaze in vampire fiction. Vision and eyes are dwelt on obsessively in ‘The Vampyre’. This led him to the development of special effects in vampire narratives. Polidori initiates an obsession with visualising the vampire in the transition from oral to print narrative (and subsequently stage and screen).

Bill Hughes discussed Lady Caroline Lamb’s novel Glenarvon (1818) – a Gothic-tinged narrative of romance and political rebellion in Ireland that refracted Lamb’s own fiery love affair with Byron. The novel’s gloomy tormented hero, Glenarvon (or Lord Ruthven) spreads dissidence in an ambivalent vampirism through his equally contagious glamour. Glenarvon provided material for ‘The Vampyre’ but also bequeathed a parallel legacy of the Byronic demon lover through Gothic romance, reuniting with the vampire in present-day paranormal romance.

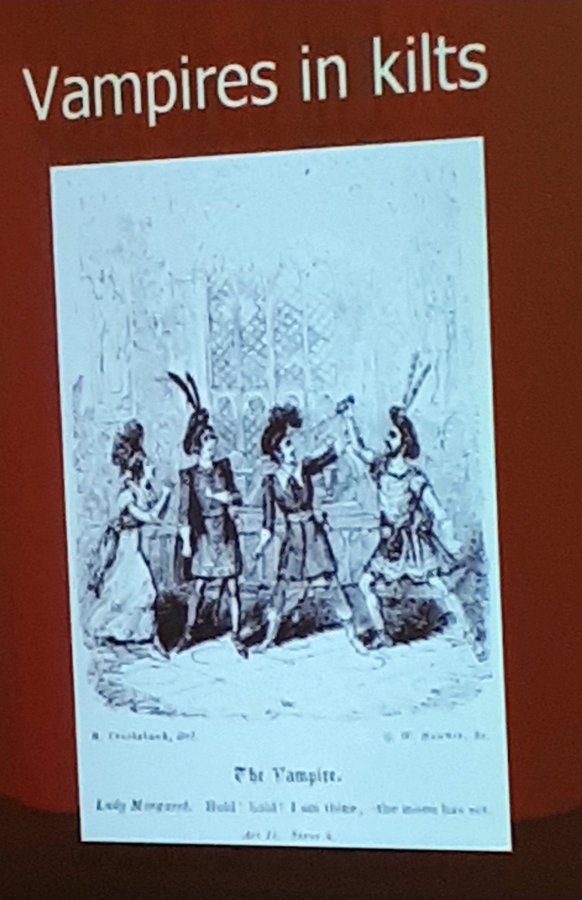

Sam George talked about the huge impact of ‘The Vampyre’ in Britain and Europe and how it was expanded in Bodard’s French novel, then staged by Planché and others. The predatory sexuality of the libertine Lord Ruthven took the vampire out of the forests into the drawing rooms. The optical stage illusions of phantasmagoria, more ghostly than the magic lantern, were a powerful device in the theatrical vampire’s success, enabling spectres to hover in the air, whereas the ‘vampire trap’ enabled actors to appear and vanish as if by supernatural agency. Planché’s version invoked Celtic traditions with its Western Isles setting—and vampires in kilts! The staged Draculas later led to the slaying kits as stage props, one of which was on display at the symposium.

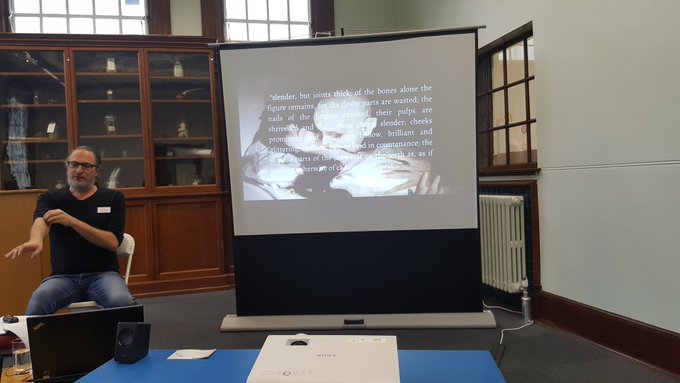

The novelist Marcus Sedgwick described how tuberculosis came to be seen as glamorous in the nineteenth century. Drawing on Susan Sontag and illustrated by the death of Chopin. Alongside the aestheticisation, the idea of diseases associated with personality types – under- or over-stimulation, licentiousness, effeminacy – but also angelic purity. The pale modern vampire, distinct from the peasant bloated with blood, shares these symptoms, including breathlessness. Thus the pale alluring vampire first sketched by Polidori is closely related to the Romantic perception of tuberculosis.

Gina Wisker talked about three vampiric texts linked with the escapist setting of a holiday resort (the genesis of ‘The Vampyre’ in that vacation at the Villa Diodati being crucial here): Florence Marryat’s ‘Blood of the Vampire’, Sarah Smith’s ‘When the red storm comes’, and Neil Jordan’s film Byzantium, based on Maria Buffini’s play ‘A Vampire Story’. With Marryatt’s vampire there are themes of racial purity and the foreign woman as fascinating exotic beauty. In Sarah Smith, the offer of transcendent love from a handsome foreign nobleman is an alternative to the carnage of World War 1. Byzantium draws on Polidori, with female vampires as companions in a male-dominated world, abused by aristocratic men. They act as angels of mercy in an age of crumbling social services in a run-down resort.

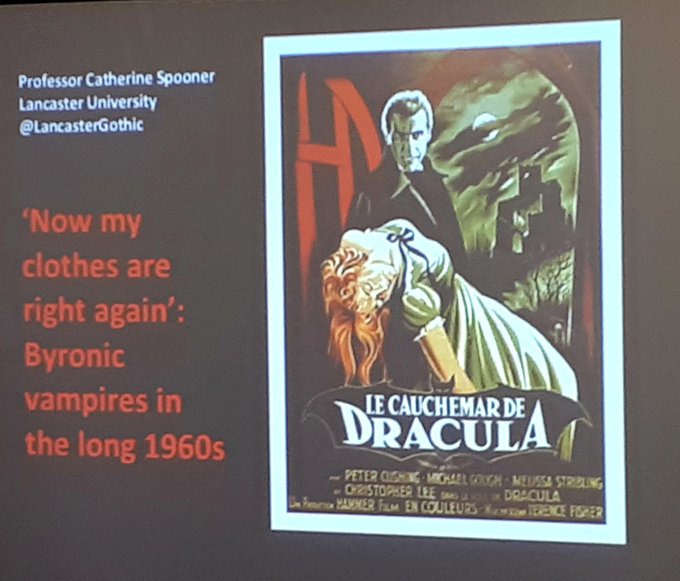

Catherine Spooner showed how Gothic themes were intrinsic to the countercultural aesthetic of the 1960s, prefiguring present-day Goth style too. The male vampire Jane Gaskell’s 1964 novel, The Shiny Narrow Grin shows the fashionable dandyism of working-class communities. The Byronic vampire flourishes – bisexuality was discussed in recent biographies of the poet and his sexual adventuring was in tune with ‘60s ideas. The satirical mode of vampirism – often as reaction to those liberal ideas – was pronounced and Hammer Films’ Dracula films often showed this. Dracula represents modernity and his antagonists a repressive Victorianism. And out of this Byronic counterculture will emerge the sympathetic vampires of Anne Rice and others.

Sir Christopher Frayling, who inaugurated academic vampire studies, ended the first day with a fascinating plenary which surveyed the development of the field, interspersed with personal reminiscences. He showed how disparate elements became consolidated into a genre with Polidori. Then he led us through his own journey from the Enlightenment and Rousseau and eighteenth-century vampire reports to his pioneering book and his friendship with Angela Carter and her love of things Gothic. He showed that there are still new ways of looking at the vampire and he offered support and hope for young researchers in the field. He also drew our attention to a big exhibition in Paris next year on the history of vampires!

We began Sunday with a tour of Highgate Cemetery, accompanied by the erudite and entertaining guides, Peter Mills and Stephen Sowerby. A Gothic site in its own right, it features in Dracula and has the graves of the Rossettis and of the groundbreaking lesbian novelist Radclyffe Hall among many others (Karl Marx lies in the East Cemetery which we didn’t have time to see). It was also the scene of a notorious vampire hoax in the 1970s.

Back at Keats House, Stacey Abbott returned to Neil Jordan’s film Byzantium. Jordan consciously evokes Polidori and is also in dialogue with Buffini’s play and Jordan’s earlier vampire film, Interview With the Vampire (1994). The vampire women interrogate the idea of the Byronic vampire; the film rewrites nineteenth-century vampires from a female perspective. Both films feature vampires who show a propensity for compassion and both explore the nature of storytelling. Rather than exploiting the weak, these female vampires serve justice and mercy and curb the power of men and the patriarchal male vampires.

Sorcha Ní Fhlainn supplemented Stacey Abbot’s reading of Jordan’s Byzantium. Polidori and subsequent vampire stories explore the nature of guilt and Jordan’s films are no exception. The Irish background is significant; for example, the stone and blood imagery from Irish myth. Jordan’s rewriting of Rice, of Polidori and Buffini is important. He also extends the queer dynamics of Polidori. Forms of narrative in Polidori – whispered secrets and oral tradition – are both exploited by Jordan.

Daisy Butcher talked about the long history of female vampires in folklore and literature, with Geraldine from Coleridge’s Christabel as a prototype. Female vampires often have empathic characteristics and are often psychic vampires. Christabel introduced a range of tropes – snake imagery; vampires dressed in white, signifying modesty and purity; an ethereal, languid body that conceals monstrosity. Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla feeds off Laura’s emotions as well as her blood. Luella Miller is parasitic, infantile, and narcissistic, but seems to have no control over her draining of people. These three texts show an increasing sympathy for the female vampire.

Kaja Franck began with Joss Whedon’s Angel as a modern incarnation of the pale, brooding Byronic vampire. Anne Rice’s Lestat and Edward Cullen of Twilight are also fashionably pale. Their appearance is central – vampires are made to be looked at: ‘The Vampyre’ has many moments of staring at, being looked at (as Ivan Phillips also noted). Twilight and ‘The Vampyre’ share certain features such as the pale outsiders, their capacity to stimulate adaptations, their status as popular culture, and the presence of a love triangle. But their difference is in having a female and male author respectively. Thus Polidori ushers in the vampiric way of looking but Twilight inverts that.

Jillian Wingfield presented on Octavia Butler’s Fledgling. From Dracula to Richard Mathison’s I Am Legend, vampire fiction has been connected to contemporary views of science. In Fledgling, vampirism is rationalised through scientific discourse. Butler transforms themes from Polidori to challenge Western male cultural biases since then. Butler’s use of science absorbs traces from both ‘The Vampyre’ and Frankenstein. There is a symbiosis of genres too.

Xavier Aldana Reyes showed us the presence of Gothic in Spanish literature as a key indicator of national culture and a non-realist tradition, traceable back to the late nineteenth century. There are blood-sucking witches in Spanish folklore but the vampire only appears after external models made them available. The first literary vampire in Spain – Emilia Pardo Berzán’s Vampiro (1901) – was influenced by Polidori and French and German Romantic texts. Spanish vampire narratives would address the coldness of aristocrats and the position of women. With the advent of cinema, vampires became more prominent. Parodies of Dracula featured heavily here and a psychosexual treatment of Carmilla stands out for its almost surrealist quality.

It was a fabulous conference and OGOM would like to thank the speakers and guests who made it possible, Keats House staff (particularly Anna Mercer and Rob Shakespeare), and the caterers with their vampyre cupcakes. We are also enormously grateful for generous funding from the British Association for Romanticism Studies, the International Gothic Association, and the University of Hertfordshire.