I’m revisiting an interesting article by Maria Nikolajeva, director of the Homerton Research and Teaching Centre for Children’s Literature, entitled ‘Young adult fiction is integral to helping students develop empathy’, ahead of the YA Investigating Identities conference at the University of Northampton next weekend. I agree with the basic premise here, and I want to argue that YA Gothic fictions, with their emphasis on otherness and outsiderness, are crucial to promoting this feeling of empathy. This was something I had in mind myself when I was creating my Generation Dead: YA Fiction and the Gothic course at the University of Hertfordshire in 2013. I disagree with statements Nikolajeva makes elsewhere however, though these are worth raising:

Sadly, young adult fiction is not always taken seriously. One of the reasons for this is that the majority of early YA novels tended to be excruciatingly didactic − pamphlets on unwanted pregnancy and peer pressure, slightly disguised as fiction.

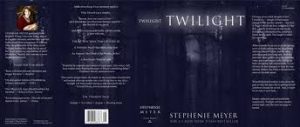

For me this argument belongs to an earlier era, one when women educationalists first began to be prominent in writings for young persons. Many in the eighteenth century were Quakers or Unitarians, Priscilla Wakefield and Anna Laetitia Barbauld etc. and later Anna Sewell, author of Black Beauty. The latter was the first novel to give voice to, and be narrated by an animal persona and it is seminal to any empathy or animal cruelty debate. The work of these teachers of girls was rejected by literary figures of the day such as Charles Lamb who branded them a ‘monstrous regiment of women’. Histories of children’s literature have similarly dismissed these products of a female pen as dreary didactics. We apparently have to wait until the 1860s when Alice was published to find books that are designed for children’s pleasure. At this point children’s or young adult literature is wrestled away from women teachers back into the hands of male academics or intellectuals (Lewis Carroll, J. M. Barrie, and later J.R.R. Tolkein and C.S. Lewis). My point is that it is often not the didactic writing that is the cause of the derision, but the feminisation and popularisation of the genre. Twilight is the stand out example of this process in the present. Whilst there are arguments to be had re: literary merit, the vitriol attached to this much maligned book is extraordinary. This derision impacted on the understanding of YA literature more broadly and shaped the prejudice I experienced re: my course on YA gothic fiction within the academy in its early stages. Even now it occasionally resurfaces at the university and can be felt in the disappointment my colleagues in literature feel when a student decides to write their dissertation on YA fiction. There is a need to talk about this misunderstanding still. I’m looking forward to some interesting debates next week!

One exemplary story in this respect is, of course, ‘Red Riding Hood’, a fairy tale which also has the werewolf motif latent within it. Here, the wolf can figure as the bestial side of humanity; importantly, sexuality is at play here as much as the violence and cunning that other wolf narratives depict. This is brought out in the multifarious variations on the tale since the classic versions of Grimm and Perrault—in Angela Carter’s wolf tales, for instance, or in numerous more frivolous retellings in popular culture.

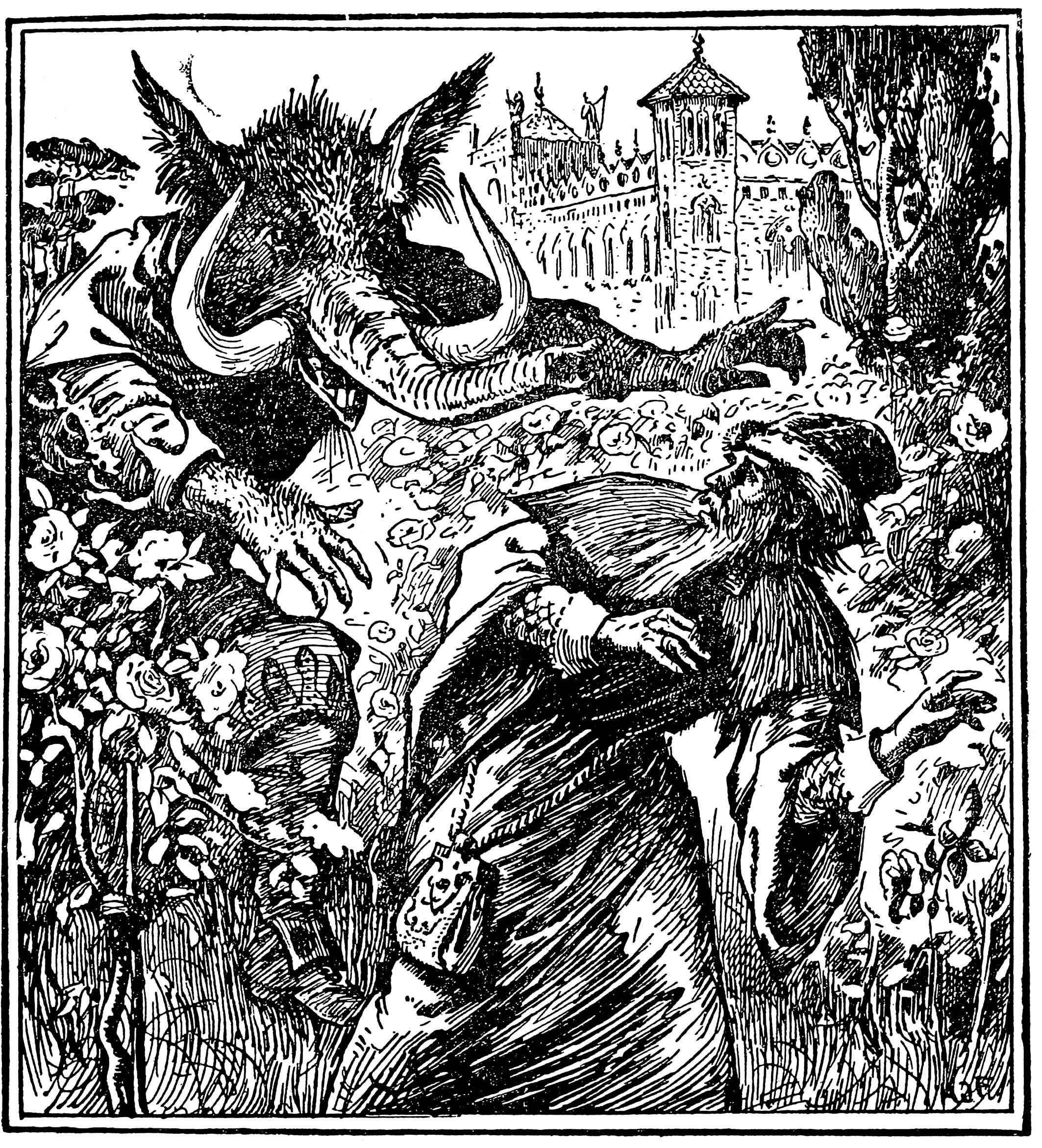

One exemplary story in this respect is, of course, ‘Red Riding Hood’, a fairy tale which also has the werewolf motif latent within it. Here, the wolf can figure as the bestial side of humanity; importantly, sexuality is at play here as much as the violence and cunning that other wolf narratives depict. This is brought out in the multifarious variations on the tale since the classic versions of Grimm and Perrault—in Angela Carter’s wolf tales, for instance, or in numerous more frivolous retellings in popular culture. I make a slight detour to consider another classic fairy tale, one which lies at the roots of the research I’ve been doing on the genre of paranormal romance: ‘Beauty and the Beast’. The Beast here is not a wolf, and he’s not described as lupine in the original story; different illustrators portray him in different ways, often leonine. Iona and Peter Opie claim that ‘Beauty and the Beast’ is ‘The most symbolic of the fairy tales after Cinderella, and the most intellectually satisfying’. Perhaps the tale lends itself more easily to allegory than most; you have the polarised qualities of hero and heroine; the abstraction of a spiritual quality, ‘Beauty’, set against the earthiness of ‘Beast’. There are hundreds of variations, adaptations, and reworkings of the basic story alone. But the theme of human and monstrous lovers also lies behind the recently emerged genre of paranormal romance.

I make a slight detour to consider another classic fairy tale, one which lies at the roots of the research I’ve been doing on the genre of paranormal romance: ‘Beauty and the Beast’. The Beast here is not a wolf, and he’s not described as lupine in the original story; different illustrators portray him in different ways, often leonine. Iona and Peter Opie claim that ‘Beauty and the Beast’ is ‘The most symbolic of the fairy tales after Cinderella, and the most intellectually satisfying’. Perhaps the tale lends itself more easily to allegory than most; you have the polarised qualities of hero and heroine; the abstraction of a spiritual quality, ‘Beauty’, set against the earthiness of ‘Beast’. There are hundreds of variations, adaptations, and reworkings of the basic story alone. But the theme of human and monstrous lovers also lies behind the recently emerged genre of paranormal romance.