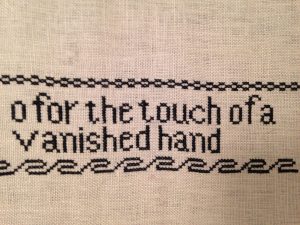

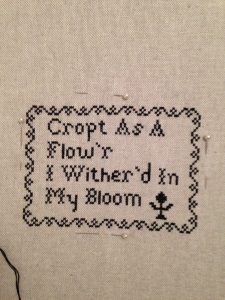

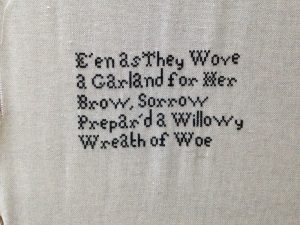

Miranda Lennon has been collecting verses from the graves of eighteenth and nineteenth-century women and embroidering them into beautiful bespoke samplers. The verses, considered mawkish or sentimental by some, convey a beautiful sensibility around death and mourning and preserve the lost language of flowers.

Miranda can be contacted at mirandalennoncostume@gmail.com. She’d love to hear from you if you are interested in these graveyard poems. She takes orders and plans to launch a website in the new year.

There is also a delightful new anthology The Language of Flowers ed. by Jane Holloway in the Everyman’s Library. Some of you will know that I have written on the language of flowers myself and floriculture (the art of pressing, moulding or embroidering flowers). Below is an extract from my book Botany, Sexuality and Women’s Writing 1760-1830: From Modest Shoot to Forward Plant (Manchester University Press, 2007), pp. 154-55. Hopefully this sheds some light on Miranda’s work and inspires further interest in women and the culture of flowers:

British flowers had come to be regarded as more appropriate symbols of purity and virtue than their foreign counterparts. Small, sweet-smelling native flowers such as the snowdrop, violet, and lily of the valley adorned the cemetery or graveside garden, whereas ornamental and showy florist flowers such as the (Turkish) tulip or the flamboyant African or French marigold would appear immodest in such a spiritual setting. Lilies of the valley and snowdrops were thought particularly appropriate for the graves of children or young women due to their association with innocence and purity; the motif of the broken lily can be found on urns and monuments commemorating young women ‘cut off in the flower of their youth’.[2] Women’s poetry often draws on these floral traditions. For example, Anna Seward’s poem ‘Eyam’ (written in 1788 and published in 1792) records the custom of hanging garlands of white flowers over the church pews of village maids who ‘die in the flower of their age’.[3]

Robert Thornton specifically selected women writers to commemorate British flowers when he united ‘beauties of the vegetable race’ from every corner of the globe, compiling a poetical empire of flora. His florilegium Temple of Flora, or Garden of Nature (1799-1807) boasts a rich array of botanical poetry by such women as Arabella Rowden, Charlotte Smith, Charlotte Lennox, and Anna Seward, among others. From this work, Cordelia Skeeles’s celebration of the common snowdrop is illustrative of the way indigenous species of flower had come to denote virtue:

Drooping harbinger of flora,

Simply are thy blossoms drest;

Artless as the gentle virtues

Mansioned in the blameless breast.[4]

Elsewhere, in the poetry of the aspiring botanist Arabella Rowden, the ‘untainted’ beauty of the native wild flower, ‘simply [. . .] drest’ and ‘artless’, is set up in opposition to the harlotry of the florists’ flower or ‘exotic’:

Seek not this flower, and its fraternal tribe,

Amid the garden’s gay luxuriant pride;

Explore the woods, the meadows, and the wild,

For Sweet Simplicity’s Untainted Child.[5]

Charlotte Smith expresses similar sentiments in a sonnet from Rural Walks: in Dialogues Intended for the Use of Young Persons (1795), written in praise of Miranda, ‘Nature’s ingenuous child’.[6] The poem is interspersed with dialogue between Mrs Woodfield and her niece Caroline, centring around two young women of very different dispositions. Maria, represented by the showy, scentless tulip, is fashionable and vain of person whereas Miranda is as ‘mild, generous and unassuming’ as the lily:[7]

Miranda! mark, where, shrinking from the gale,

Its silken leaves yet moist with morning dew

That fair faint flower, the Lily of the vale,

Drops its meek head, and looks, methinks like you![8]

The retiring lily provides a stark contrast to the forward florist’s tulip:

With bosom bar’d to meet the garish day,

The glaring tulip, gaudy, undismay’d`

Offends the eye of taste, that turns away,

And seeks the Lily in her fragrant shade.[9]

‘[W]rapp’d in its modest veil of tender green [. . .] and bending, as reluctant to be seen’, the native lily of the valley evokes the realm of the private and virtuous; in contrast, the exotic tulip symbolises the wantonness which was commonly associated with highly public women.[10] The laws of sexual conduct are learned through dialogues on flowers and the feminisation of botany in relation to the gendered dichotomy of the public and private spheres again reveals itself.

[1] Maria Jacson, A Florist’s Manual (London: Henry Colburn, 1816), p. 3.

[2] According to Nicholas Penny, the motif of the broken lily can be found on a marble urn at Harefield in Middlesex to commemorate Diana Ball who died aged 18 in 1765. Penny states that ‘there are several other late eighteenth-century monuments which use this motif. But it was popularised by Westmacott, usually in monuments to children, maidens or young wives ‘cut off in the flower of their youth’ (Church Monuments in Romantic England (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1977), p. 33).

[3] Anna Seward, note to ‘Eyam’ (41-48), in Roger Lonsdale (ed.), Eighteenth-Century Women Poets (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), p. 317.

[4] Cordelia Skeeles’s untitled poem, in Thornton’s text ‘The Snow-Drop and the Crocus’, is printed opposite the coloured plate of the snowdrop in Robert Thornton, New Illustration of the Sexual System of Carolus von Linnaeus (London: T. Bensley, 1807). unpag.

[5] Frances Arabella Rowden, ‘Violet’, in A Poetical Introduction to the Study of Botany (London: T. Bensley, 1801), p. 114.

[6] Charlotte Smith, [sonnet to Miranda], Rural Walks: in Dialogues Intended for the Use of Young Persons, 2nd edn, 2 vols (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1795), i, line 14, p. 130.

[7] Smith, Rural Walks, i, p. 129.

[8] Smith, ‘Sonnet’, Rural Walks, i, lines 1-4, p. 128.

[9] Ibid., lines 9-12, p. 128.

[10] Ibid., lines 5 and 7, p. 128. Cultivated varieties of tulip were grown solely for competition or show and were often likened to immodest women who are seen to make a spectacle of themselves.