‘Is he a ghoul or a vampire?’ I mused. I had read of such hideous incarnate demons’ (Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights, Ch. 34)

Like many others, I suspect, I’ve just started rereading Wuthering Heights. And I’m frequently seeing the admonition that too many of those who love this psychological novel of extreme love, saturated with the Gothic, are simply reading it wrongly. The novel, it is said, is not the classic romantic tale such readers think it is; Heathcliff and Catherine are monsters whose relationship is full of violence, narcissism, and abuse, and not the ideal love between the sexes people mistake it for.

And of course, the passion dramatised in Wuthering Heights really is cruel, selfish, and destructive (and intertwined with notions of class, race, and power). Yet I think we may dismiss the naïve reading too easily. We should ask why so many readers do see the novel as quintessentially romantic, why adaptations such as William Wyler’s 1931 film with Laurence Olivier and Merle Oberon unhesitatingly portray it as romance; why we find the dark, brooding Heathcliff and the wild, heedless Catherine sexy and fantasise them as perfect lovers. We should not ignore the pleasures to be found in this romance – for it is a romance – and (with a handful of other narratives) is the basis for a formula that is to be found in countless romantic fictions since. I favour pitting a redemptive reading of the novel as romance fiction against the ‘hermeneutics of suspicion’ of Paul Ricoeur, though engaging with it.

Gothic Romance

That narrative of dark and dangerous passion is repeated in the genre known as Gothic Romance, which flourished from (roughly) the 1950s to the 1970s, typified by writers such as Mary Stewart, Victoria Holt, Barbara Michaels, and Madeleine Brent, stemming from Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938) – itself in some ways also a disturbingly unromantic tale. It is still found in the romantic fiction of Mills and Boon, despite their reformulation every decade to adapt to contemporary values: current products from this publisher feature strong-willed heroines with a career who yet still melt finally into the powerful arms of their brooding, even raging lovers. It is found in the recent reincarnations of Gothic Romance as paranormal romance and romantasy, where the metaphorical vampirism of Heathcliff (and his Byronic ancestors) becomes literal and the romance is spiced up by the added danger that the passionate lover’s bite may drain you of your blood; you may be torn to pieces by his wolfish fangs; a wild waltz with him may end with you enchanted and stolen to Faerie. It is notable that the Young Adult vampire romance Twilight (2005) (widely condemned for its representation of romance as acquiescence with patriarchal domination and even abuse) pointedly shows Bella Swan reading Wuthering Heights. The latter novel thus figures as a signifier for the idealised romantic love that Twilight is supposed to embody. (This metafictional device features in other paranormal romances.)

So, Wuthering Heights really is romantic fiction, and a key link in an intertextual chain of writing and rewriting passionate love over a couple of centuries. Reading it thus, placing it within a generic field can, I argue, better reveal the true nature of romantic passion in general – understanding its instinctual dynamics, its modulation by social forces, its dangers and pleasures, and even perhaps its utopian potential. We can observe and immerse ourselves in the play of egotism and the nihilation of the self; the revolt against convention and the submission to oppressive ideologies; asocial irrationality and Gothic enchantment against stifling instrumental reason; freedom and compulsion; Eros and Thanatos. Wuthering Heights is of course more self-aware than many romance novels and allows all these various and contradictory facets to emerge in a play of dangerously intoxicating pleasure. We need to read these fictions and even romance itself with the perspective of Fredric Jameson, holding both the ideological and the utopian aspects together; noting how they may form part of the mechanism of oppression while opening up in the imagination ways of emancipation.

Adaptation

I am of course rereading Wuthering Heights, as I’m sure others are, because of the appearance of Emerald Fennel’s film ‘Wuthering Heights’ (the quotation marks are significant). I’ve not seen the film yet but have seen the wildly diverging reviews and followed the heated debates on social media. I have an uneasy relationship with adaptations of classic texts, especially ones I love (don’t get me started on Jane Austen!). And yet I may be in the wrong. One should be able to detach oneself from the source that is adapted (the ‘hypotext’, in the terminology of Gérard Genette). There can be a scholastic conservatism that resists new interpretations; there can also be a superficial revisionism that has scant respect for the original and glibly discards its complexities. I don’t suspect this new film of the former. The most vivid reworkings avoid both an arid historicism and a facile presentism.

The second part of the novel is rarely taken up in adaptations. There, an alternative model of an undistorted, mutual, more irenic romantic love appears. It is a love that is social and comfortably adapted to the Reality Principle. But it is the first generation of lovers that more readily captures readers’ souls. It is the wild passion in a bleak landscape and the desperate yearning from beyond the grave that inspires Kate Bush’s eponymous song, which ‘misinterprets’ the novel as romance fiction in an inspired manner.

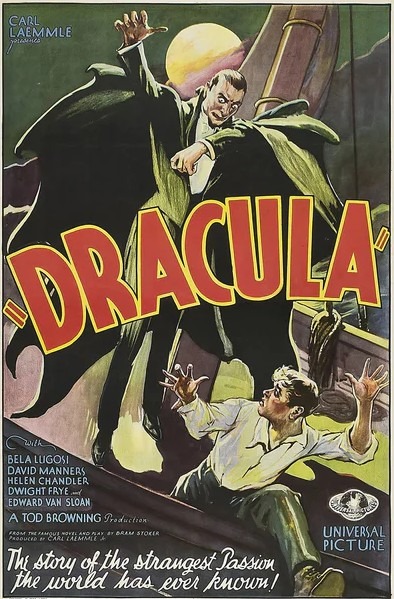

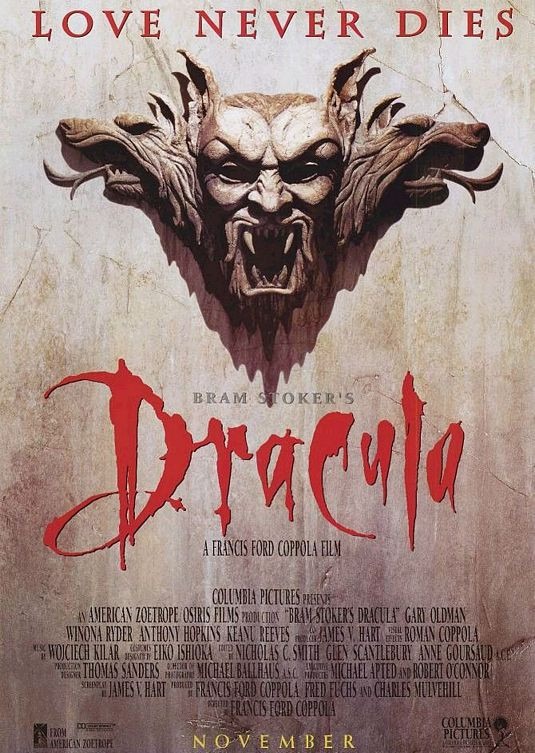

Cinematic adaptations of the novel likewise have made these themes central. The trailers for Wyler’s and Fennel’s film both signal their generic affiliation to romance in almost the same words: ‘The greatest love story of our time . . . or any time!’, proclaims the 1939 trailer, while the 2026 film is ‘Inspired by the greatest love story of all time’. And the motif of eternal love transcending death is one of the devices that modulates the transmutation of the vampire narrative from Gothic horror into paranormal romance. This is suggested even in Tod Browning’s early adaptation of Dracula (1931); one poster for the film announces ‘The story of the strangest passion the world has ever known’, which could just as easily fit Wuthering Heights. But this submerged romantic theme comes fully to the fore in Frances Ford Coppola’s 1992 Bram Stoker’s Dracula, whose depiction of Count Dracula as tormented lover, grieving his dead love for eternity ‘across oceans of time’ surely echoes Heathcliff (whom Nelly Deans thinks of as ‘ghoul or vampire’). The posters for this film insist that ‘Love never dies’. (The plot device of Mina Harker as Dracula’s reincarnated lover has been employed since in quite a few paranormal romances. Mina reappears, too, ‘After centuries of waiting’, says the trailer, in the new Dracula directed by Luc Besson, which promises to be equally romantic.)

Wuthering Heights is now almost mythical material – a core myth, in fact, of the genre of romantic fiction (and such associated genres or subgenres as romantasy, paranormal romance, and historical romance). Just as there are many Antigones and countless revisionings of the Faust tale, and as Wuthering Heights itself reworks folklore and other texts, there are many possible avatars of Wuthering Heights (not all sublime; see the 1996 musical with Cliff Richard). (There’s a list here of some of the film and TV adaptations; Jacques Rivette’s Hurlevant (1985) should be there too, along with other non-Anglophone versions mentioned in this article.) I should really watch the new film with the attitude of encountering yet another retelling of a powerful myth of desire, death, and power (and everything else that this fabulous novel contains), and as a distinctive artefact in its own right.

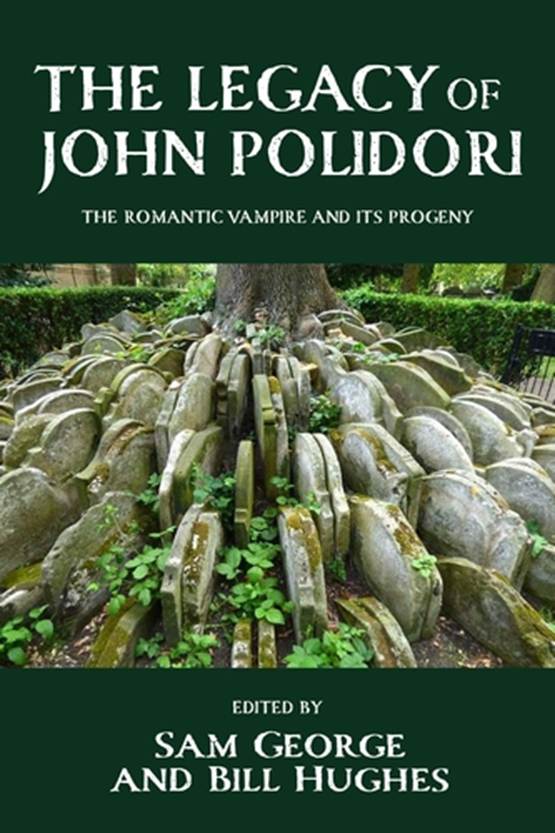

Our research with the Open Graves, Open Minds Project centres upon the transmutation of genres, often including their folkloric and mythical origins. We are fascinated by the notion of Gothic enchantment, where enchantment may be the terrifying enthralment and bondage to an alien power, or an illuminating force that emancipates us by opening up new vistas. The rich ambiguities that give Wuthering Heights its magical power and entrance us with a vision of preternatural romantic love, provide a fine example of such Gothic enchantment.