Stacey Abbott has long been a friend of, and collaborator with, OGOM, presenting inspiring keynotes at our conferences and contributing excellent chapters to our books. Here, she reviews the Scharf-Gerstenberg Collection’s recent exhibition in Berlin celebrating 100 years of F. W. Murneau’s classic 1922 vampire film, Nosferatu. (OGOM hosted our own tribute to Nosferatu, where Stacey was one of the presenters; this was a significant event in what we celebrated as the Year of the Vampire .)

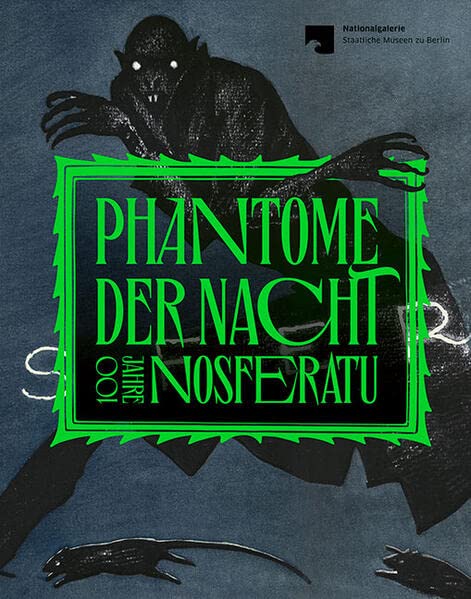

Phantome Der Nacht: 100 Jahre Nosferatu/Phantom of the Night: 100 Years of Nosferatu

16 December 2022 – 23 April 2023, Scharf-Gerstenberg Collection, Berlin

2022 marked the centenary of the much-loved master vampire film by F. W. Murnau, Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922). A landmark of German Expressionist and horror cinema, as well as being the earliest surviving adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), this anniversary was met with numerous celebration screenings and publications, marking its significance and influence. These symposia included an in-person day event at City Lit in London, the online Horror Reverie Event hosted by the Monstrum Society of Montreal, and of course OGOM’s own online symposium: Nosferatu at 100: The Vampire as Contagion and Monstrous Outsider. Each of these events and publications brought together a diverse range of scholars, programmers, writers, filmmakers, and critics to discuss and reflect on the film’s influence on cinema language, developments in the horror and gothic genres, and its legacy on the vampire in film, literature, and television.

To conclude these centenary celebrations, the Nationalgalerie of Berlin hosted an exhibition on the film at the Scharf-Gerstenberg Collection, which ran from 16 December 2022 to the 23rd April 2023 and was curated by Jürgen Müller, Frank Schmidt, and Kyllikki Zacharias. I was able to close my own celebrations of the film by visiting this exhibit in April. Walking into the atmospheric and cavernous space at the Sharf-Gerstenberg Collection, I felt a bit like Hutter as he crossed the bridge and entered the land of the shadows. It is a haunting place and an ideal location for this exhibition. For instance, in one room a reflective beaded curtain was hung from an arched passageway between rooms, onto which the image of Orlok, appearing from and then retreating into the shadows, was projected. Patrons were then invited to follow Orlok into the darkness as they passed through the curtain. This was an inspired and chilling use of the space and a reminder of how important Murnau’s use of mise-en-scene and real locations was to his re-conception of the German Expressionist aesthetic. The horrors of the vampire were literally projected onto the walls.

In terms of the content of the exhibit, I was delighted to discover that there is much still to discover about this often-discussed masterpiece. The exhibit was structured as a journey through the film’s narrative from the idyllic representation of family and home in Wisborg to the spreading of the vampire plague and the eventual destruction of Orlok in the sunlight. Each room projected key images and scenes from the film onto the walls alongside paintings by artists from which director Murnau and producer/art director Albin Grau drew inspiration, including Edvard Munch, Max Klinger, Félicien Rops, Georg Friedrich Kersting, Francisco de Goya, and Henry Fuseli. This juxtaposition enabled me to see these familiar images with fresh eyes, highlighting the dynamic play with light and shadow in F.A Wagner’s cinematography; the baroque and Gothic qualities of Grau’s set design; and the beauty and richness of Murnau’s compositions. The monstrous appearance of Max Schreck as Count Orlok was richly presented alongside Hugo Steiner Prag’s haunting illustrations for the manuscript of Gustav Meyrink’s Der Golem (1916) as well as Franz Sedlacek’s Der Träumer (1912) and Stefan Eggeler’s The Plague of Pestilence (1921), putting Schrek’s depiction of the master vampire into a broader context of images of monsters and faces of death. These images, as noted in the programme, provided ‘visual inspiration for Nosferatu’s darkly triumphant entry into the streets of Wisborg’. Through references to André Breton and Salvador Dali, the exhibition also highlighted the film’s influence on the Surrealists, in particular the dream-like reverie of Count Orlok’s land of shadows. Through the juxtaposition of vast array of imagery, including paintings, illustrations, engravings, frame shots, lobby cards, and promotional material from the film’s original release, the curators have drawn together a range of material that demonstrates that Nosferatu is not only an important milestone of cinema and horror history but is part of a rich and varied heritage of European visual art.

One of the key discoveries for me was the Austrian graphic artist Alfred Kubin whose work is interwoven throughout the exhibit. The curators argue that Kubin’s style and subject matter was an important influence on Grau’s designs for the film, in particular his depiction of the dominion of the vampire. His paintings, illustrations, and designs are macabre and brooding, featuring depictions of lonely, isolated landscapes, predatory beasts, plague, and death; an ideal expressionist model for the film. The curators note that Kubin was at one point meant to design the sets for The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919) and while this did not happen, they convincingly demonstrate through this exhibition that his work is a significant visual referent for the depiction of Stoker’s master vampire. The juxtaposition of Orlok raising from his coffin and Kubin’s Der Kardinal [The Cardinal] (1919) reclining in prayer offers a clear demonstration of the visual similarities and expressionist influences, while Kubin’s paintings Das Rattenhaus (1902) and Seuche [Epidemic] (1902), provide visual context for the film’s preoccupation with rats and plague contamination, particularly as the film was made so soon after the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918. The funnel through which Kubin’s work bled into Nosferatu is of course Albin Grau. Grau’s contribution to the film as a set designer is highlighted throughout the exhibit. The display of his previous design work, company logo, set illustrations, and promotional material, showcase his keen eye and expressionist vision for the film. His illustrations of the monstrous and rat-like Count Orlok have becoming increasingly available through recent DVD and Bluray releases of the film by the British Film Institute and Eureka. But seeing a full collection of these illustrations all together on display alongside the film highlighted the visceral power of Orlok’s monstrosity and the significance of Grau’s contribution to the film’s legacy. A full collection of images from the exhibit can be found through the lengthy programme published to coincide with the exhibition. It is a beautiful publication.

Phantome Der Nacht was a wonderful conclusion to Nosferatu’s centenary celebrations and served as a reminder of the richness of this masterful film and the visual synergies between Expressionist Art and Gothic and Horror Cinema.

Stacey Abbott is the author of Celluloid Vampires (University of Texas Press 2007), Undead Apocalypse: Vampires and Zombies in the 21st Century (Edinburgh University Press 2016), and the BFI Film Classic on Near Dark (Bloomsbury 2021).