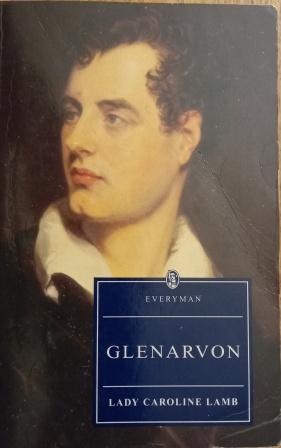

Lady Caroline Lamb, whose birthday it would have been on 13 November (I’m a bit late!), famously judged Lord Byron ‘Mad, bad, and dangerous’, having had a brief and tempestuous affair with him. This relationship inspired her novel Glenarvon (1816), which is usually read as a roman à clef which enacts revenge on Byron and, with its sharp satire on her own social circle, led to scandal and her public shaming. Lamb, who was a fine mimic of Byronism (and Byron himself) was herself perhaps a little mad, denounced as bad, and had an aura of danger about her.

But Glenarvon can be read as more than an act of personal revenge. It’s a compelling (though wild and excessive in parts) Gothic novel that also delves into political issue, particularly with its setting of the Irish Rebellion of 1798. The Byronic figure of the titular hero, Glenarvon, also known as Lord Ruthven, serves as a critique of Byron’s own ambivalent radicalism (and of his Whiggish peers). And the social satire is acute and very amusing.

Glenarvon is characterised with the melancholy nobility and satanic allure of the classic Byronic hero; he is ‘arch fiend’ and ‘fallen angel’, and howls at the moon (his ancestor drinks blood from a skull). He takes part in the anti-colonial Irish Rebellion, inciting the people with his rhetoric and personal charm. Glenarvon’s political persuasiveness is linked to his sexual glamour. Glenarvon’s women themselves become Byronic, denouncing God, family, and society, and swearing satanic vows of abjuration; Byronism is an infection, like vampirism. Glenarvon ultimately betrays both his women lovers and Ireland, yet remains an inspirational force, though the rebellions of transgressive women and nation are both doomed. With all these conflicting forces, Lamb’s novel shifts between an anti-Jacobin stance and radicalism.

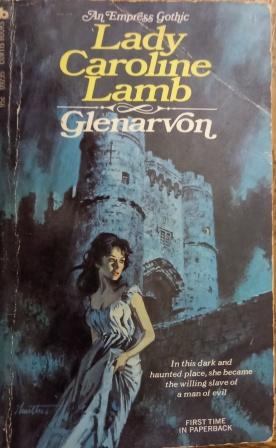

John Polidori took the name Lord Ruthven for his creation of the first vampire in English prose fiction, possibly his own revenge on Byron, in the novella The Vampyre (1819). Glenarvon himself anticipates the vampirism of his avatar in Polidori and also a whole strand of Gothic-tinged fictions that feature a seductive demonic lover as hero, from the Brontës, through the Gothic Romances initiated by Daphne du Maurier that peaked during the 1970s, to the vampiric lovers in contemporary paranormal romance such as Stephenie Mayers’s Twilight. So it’s not as inappropriate as it seems to see Glenarvon in this dramatically kitsch cover, an edition from 1973 in the Empress Gothics series. (Compare this to these Gothic Romance novels discussed here.)

Lady Caroline Lamb’s own colourful and emotionally fraught life, even without the self-dramatisation she performs in Glenarvon, had enough wildness and pathos to furnish a romance story – as this 1968 novel by Eva McDonald shows. Yet, with its clumsy appropriation of Lamb’s life as a contrived subplot to the dreadful main story, this is not the best tribute to her neglected genius.

Polidori’s revision of Ruthven strips away Lamb’s ambivalence, but by clearly marking the aristocratic demon lover as both Byronic and a vampire, inaugurates a literary archetype. Yet many of Ruthven’s descendants, both those that are only metaphorically vampiric and the more explicit incarnations in paranormal romance, resurrect the alluring mix of rebellion and faithlessness that Lamb depicted. I will be writing on this in a chapter in OGOM’s forthcoming book, The Romantic vampyre and its progeny: The legacy of John Polidori, edited by myself and Sam George. This book comes out of our 2019 symposium, ‘Some curious disquiet’: Polidori, the Byronic vampire, and its progeny. We now have the contract for this with Manchester University Press and I promise it will be very exciting – more details soon!