Vampire’s rebirth: from monstrous undead creature to sexy and romantic Byronic seducer in one ghost story

Sam George, University of Hertfordshire

Victorian physician John Polidori took the vampire out of the forests of eastern Europe, gave him an aristocratic lineage and placed him into the drawing rooms of Romantic-era England. His tale The Vampyre, published 200 years ago – on 1 April 1819, was the first sustained fictional treatment of the vampire and completely recast the folklore and mythology on which it drew. The vampire figure abandoned its peasant roots and left its calling card in polite society in London.

The story emerged out of the same storytelling contest at the Villa Diodati that gave birth to that other archetype of the Gothic heritage, Frankenstein’s monster. Present at this gathering were Polidori (then Byron’s physician) as well as Mary Godwin, the author of Frankenstein, Claire Clairmont, Mary’s stepsister, Mary’s soon-to-be husband Percy Shelley, and – crucially – Lord Byron.

Read more: Fantasmagoriana: the German book of ghost stories that inspired Frankenstein

Byron’s contribution to the contest was an inconclusive fragment about a mysterious man, Augustus Darvell, characterised by “a cureless disquiet”. Polidori took this fragment and turned it into the sensational tale of the vampire Lord Ruthven, preying on the vulnerable women of society.

After its magazine debut the story was published in book form and went through seven English printings in 1819 alone. It was adapted for the stage the following year by melodramatic playwright James Robinson Planché, one of a growing number of vampire theatricals inspired by Polidori, such as those by Charles Nodier and others.

It was then expanded into a two-volume French novel by Cyprien Bérard, Lord Ruthwen ou les vampires. By 1830 it had been translated into German, Italian, Spanish, and Swedish.

Despite all these imitations and adaptations, “Poor Polidori”, as Mary Shelley liked to call him, has all but been forgotten and his lively tale has often been dismissed as a crude narrative, written under the influence of a greater, more subtle talent, Byron. And yet it was Polidori not Byron who succeeded in founding the entire modern tradition of vampire fiction.

Peasant to patrician

The vampire prior to this had been a blood-gorged, animalistic monster of the Slavic peasantry. In his study of the origins of Vampire lore, Vampires, Burials and Death, American scholar Paul Barber described the traditional image of the undead bloodsucker thus:

with long fingernails and a stubbly beard […] his face ruddy and swollen. He would wear informal attire — a linen shroud – and would look for all the world like a dishevelled peasant.

Polidori transformed the East European peasant vampire of old into a pale-faced, dead-eyed, licentious English aristocrat. This deceiving, dashing and cursed creature was in possession of “irresistible powers of seduction”, haunting the drawing rooms of Western society undetected. In the hands of Polidori, under the influence of Byron, vampires transitioned from dishevelled peasants into alluring, seductive aristocrats in the 19th century.

This elevation in social status is not all. Polidori’s The Vampyre is responsible for a number of groundbreaking innovations. He established links to the aristocracy – where there had never before been an urban vampire, let alone one as educated and high in social rank. He also introduced the notion of the vampire as sexual predator, showing his readers, for the first time, the vampire as rake or libertine – a real “lady killer”. As he wrote in his novella:

The guardians hastened to protect Miss Aubrey; but when they arrived, it was too late. Lord Ruthven had disappeared and Aubrey’s sister had glutted the thirst of a VAMPYRE!

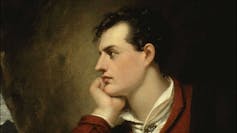

Mad and bad

Lord Ruthven is a satirical portrait of Byron as a seducer of women in polite society. “Mad, bad, and dangerous to know” – as the aristocratic writer Lady Caroline Lamb described the lover who had spurned her. This is the image we have of the vampire. Lamb cast Byron as the dark and duplicitous Gothic seducer, Lord Ruthven in her 1816 novel Glenarvon. In turn, Polidori took the name Lord Ruthven in order to create the first literary vampire.

Lord Ruthven spawned a series of saturnine or demonic lovers in turn, from the Brontës’ Mr Rochester to the more sexy incarnations of Dracula and the contemporary paranormal romances of mortal women seduced by brooding bad and dangerous vampires.

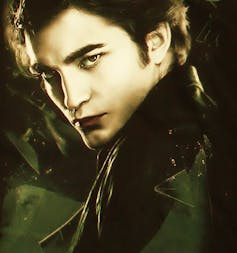

Polidori’s vampire, despite being something of a blank canvas, is sexualised and mesmeric, providing a template not only for Count Dracula but for the “Byronic hero” that features in Gothic romance from pre-Victorian times down to present-day paranormal romances such as Twilight. Edward Cullen – played by Robert Pattison, continuing the tradition of British actors playing vampires from Christopher Lee to Gary Oldman – is a reproduction of this earlier archetype. He’s something of a consumerist fantasy – as expensive as diamonds, marble or crystal:

His skin white […] literally sparkled, like thousands of tiny diamonds were embedded in the surface. He lay perfectly still in the grass, his shirt open over his sculptured incandescent chest, his scintillating arms bare […] a perfect statue carved in some unknown stone, smooth like marble, glittering like crystal.

Cullen’s aristocratic charm and anachronistic way of speaking (“I endeavoured to secure your hand” he tells Bella) indicate he is a relic of earlier models of vampiric masculinity, further evidence of the long-reaching legacy of Polidori’s vampire.

As Catherine Spooner, Professor of Gothic Literature at Lancaster University, has argued in a collection of essays about Vampires – Open Graves, Open Minds: Representations of Vampires and the Undead which I co-edited in 2012: “Over a period of about 200 years vampires have changed from the grotty living corpses of folklore to witty, sexy, super achievers.”

Polidori died in London in August 1821, weighed down by depression and gambling debts. It is said that he committed suicide by means of cyanide but that, to protect his family’s name, the coroner gave a verdict of death by natural causes. Sadly he wasn’t to know the fame his creation would achieve as the star of hundreds of books, plays and films – and millions of nightmares.![]()

Sam George, Senior Lecturer in Literature, University of Hertfordshire

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Discover more from Open Graves, Open Minds

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Whoah… wow… 200 years? That is totally fascinating. It makes me feel like I’ve been part of a big cycle adding up to the same numbers. Thank you!