On-line MA ‘Reading the Vampire’ Module

‘Reading the Vampire’ can be taken as a stand-alone course in September 2023 and will enable you to get involved with the Open Graves, Open Minds Project. The module developed out of the first ever international academic conference on vampire studies, hosted by OGOM at the University of Hertfordshire in 2010: Vampires and the Undead in Modern Culture. Taking this module opens a pathway to further research in Gothic Studies, including the PhD programme at the University of Hertfordshire.

You can also take the vampire module as part of the on-line MA Literature and Culture at the University of Hertfordshire (a one year full-time programme, or part-time over two years). Engagement will focus on themes at the forefront of contemporary culture, including identity politics, Otherness, and the environment. The modules include ‘Earth Words: Literature, Place and Environment’; ‘US Culture and #BlackLivesMatter’; ‘Networks of Modernism’.

‘Reading the Vampire’ is now in its tenth year. There has been a lot of media interest in the course down the years from The Wall Street Journal to The Guardian‘s University Sinks Its Teeth Into Vampire Fiction. Prospective students started letting us know how excited they were about the course right from its beginnings:

I can’t even express how badly I wish I could take this course. Maybe I am just a big vamp-geek, but the idea of taking an intellectual look at vampire fiction throughout time makes me so giddy that I want to bounce around like a six-year-old on caffeine pills.

Simon Midgley allowed us to discuss vampires in academe and Masters’ studies in vampire fiction in The Times, and the article featured comments from two of the ‘Reading the Vampire’ MA students. You can read more here: The Times ‘Counting on Dracula’

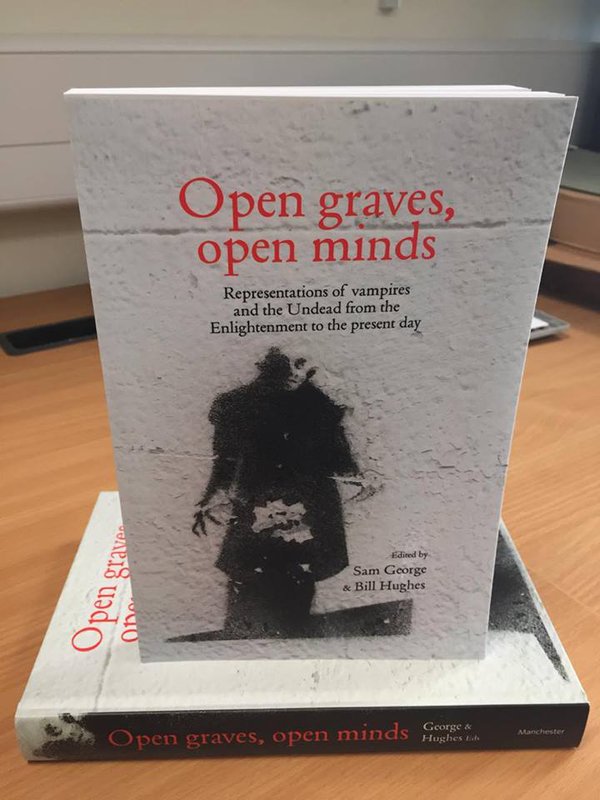

If you are interested in finding out more about vampire studies, Dr Sam George’s article How Long Have We Believed In Vampires? is a good place to start. Sam is the tutor on the vampire module and this short piece raises some useful questions to begin with. You might like to follow this up by looking at the Open Graves, Open Minds vampire book, Representations of Vampires and the Undead From the Enlightenment to the Present Day, the leading text book for the module, edited by Dr Sam George and Dr Bill Hughes. Below is a detailed guide to the ‘Reading the Vampire’ workshops should you wish to enrol and embark on your own vampire research journey. The course is 12 weeks long and has been taught via two-hour weekly workshops; the delivery online will be flexible and respond to the requirements for blended learning.

Module Outline: Reading the Vampire: Science, Sexuality and Alterity in Modern Culture

Since their animation out of folk materials in the nineteenth century, vampires have been continually reborn in modern culture. They have enacted a host of anxieties and desires, shifting shape as the culture they are brought to life in itself changes form. Reading the Vampire embeds vampires in their cultural contexts, exploring their relationship to folklore and modernity. The module will provide a forum for the development of innovative research and examine these creatures in all their various manifestations and cultural forms.

Part One: Vampires Pre-Stoker

Week 1 ‘Vampiric Origins: National Identity and Social Class from the Peasant to the Aristocrat’ [part one: ‘The folkloric vampire’]

Workshop texts: extracts from Dom Augustin Calmet, Treatise on the Vampires of Hungary and the Surrounding Regions (English trans. 1759); Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, ‘Voyage to Levant’ (1702), in Christopher Frayling, Vampires: Lord Byron to Count Dracula (London: Faber & Faber, 1991), pp. 87-103. We will start by asking How Long Have We Believed in Vampires? We will discuss the representation of vampires prior to Stoker in relation to debates around ethnicity, national identity and social class using the texts above and Marie Helene Huet’s, ‘Deadly Fears: Dom Augustin Calmet’s Vampires’, Eighteenth-Century Life, 21 (1997), 222-32 and G. David Keyworth, ‘Was the Vampire of the Eighteenth Century a Unique Type of Undead-Corpse?’, Folklore, 117 (December 2006) as a starting point. We’ll also ponder over some early definitions in the OED, the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1888), and Katharina M. Wilson, ‘The History of the term “Vampire”’, in Alan Dundes ed. The Vampire: A Casebook, pp. 3-12.

Week 2 ‘Vampiric Origins: National Identity and Social Class from the Peasant to the Aristocrat’ [part two: ‘The fictional Byronic vampire’]

Workshop texts: Lord Byron, Augustus Darvell( 1819); John Polidori, ‘The Vampyre’ (1819), in John Polidori, The Vampyre and Other Tales of the Macabre, ed. by Robert Morrison and Chris Baldick (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), pp. 1-23, 246-251. We examine the arrival of the Romantic Byronic vampire in fiction and interrogate differing perspectives on the textual relationship between Byron and Polidori. We will begin with The Vampire’s Rebirth from Monstrous undead creature to Romantic/Byronic seducer and investigate Byron as a real life model for this new aristocratic vampire, alongside issues of nationality and social class. The following articles will inform our discussion: L. Skarda, ‘Vampirism and Plagiarism: Byron’s Influence and Polidori’s Practice’ ; ‘Conrad Aquilina, ‘The Deformed Transformed; or, from Bloodsucker to Byronic Hero – Polidori and the Literary Vampire’, in Open Graves, Open Minds, pp. 24-39 ; Ken Gelder, ‘Vampires in Greece: Byron and Polidori’, in Reading the Vampire, pp. 24-41; Mair Rigby, ‘Prey to some cureless disquiet”: Polidori’s Queer Vampyre at the Margins of Romanticism’. We conclude with a discussion around a ‘Vampire Timeline’ which identifies literary vampires post-Byron and pre-Dracula (1897).

Week 3 ‘Black Vampires and Undead Brides: Stage Plays & Victorian Short Fiction’

Workshop texts: J. R. Planché, ‘The Vampyre, or Bride of the Isles’ (1820); in Beyond the Count: The Literary Vampire of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, ed. by Margo Collins (Bathory Gate Press, 2015); Ernst Raupach, ‘Wake Not the Dead’ (1823); Uriah Derick D’Arcy (pseudonym), ‘The Black Vampyre’. This week we focus on the the progeny of the Romantic vampire; the female vampire makes an appearance as does the first black vampire. We examine the influence of Polidori and the vampire in Victorian melodrama prior to the Count’s appearance with all his theatrical tropes in Stoker’s Dracula.

The following material will be inform our discussions: Katie Bray, “A Climate More Prolific in Sorcery’: The Black Vampyre and the Hemispheric Gothic’; American Literature (2015) 87 (1): 1–21; Carol A. Senf, ‘Daughters of Lilith: Women Vampires in Popular Culture’, The Blood Is The Life, pp. 199-217; Katie Harse, ‘“Melodrama Hath Charms”: Planché’s Theatrical Domestication of Polidori’s “The Vampyre”’, Journal of Dracula Studies, 3 (2001), 3-7 ; Ronald Macfarlane, ‘The Vampire on Stage’, Comparative Drama, 21 (1987), 19-33 ; Roxana Stuart, Stage Blood: Vampires of the Nineteenth-Century Stage, pp. 41-91 .

Week 4 ‘Victorian Bloodsuckers: Varney the Vampire and Karl Marx’

Workshop texts: James Malcolm Rymer, Varney the Vampire, 1845-47, Book One (Berkeley, New Jersey: Wildside Press, 2000) [extract available in Christopher Frayling, Vampyres, pp. 145-161]; Vampires in Marx’s writings, including extracts from his 1847 lectures, Capital and The Eighteenth Brumaire [handout]. This week we go in search of The English Vampire and look at the influence of the Penny Dreadful and the serialisation of Varney the Vampire in relation to vampiric metaphors in Marx’s writing, particularly the 1847 lectures which coincide with the serialisation of Varney.

See ‘Varney’s Moon’, in Nina Auerbach, Our Vampires Ourselves, pp. 27-37; S. Hackenberg, ‘Vampires and Resurrection Men: The Perils and Pleasures of the Embodied Past in 1840s Sensational Fiction’, Victorian Studies, 52 (2010), 63–75; ‘Vampires and Capital’, in Ken Gelder, Reading the Vampire, pp. 17-25 or Chris Baldick, ‘Karl Marx’s Vampires and Grave Diggers’, In Frankenstein’s Shadow, pp. 121-140, for our workshop discussions.

Week 5 ‘Vampire Lovers: Sexuality, Irishness and the Uncanny’

Workshop texts: J. Sheridan Le Fanu, Carmilla (1871-2) ed. by Jamieson Ridenhour (Kansas: Valancourt Books, 2009) or in Le Fanu, In a Glass Darkly, ed. by Robert Tracy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), pp. 243-319; Sigmund Freud, ‘The Uncanny’, in Literary Theory: An Anthology, ed. by Rivkin Julie and Michael Ryan, 2nd edn (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004), pp. 418-30. Le Fanu’s lesbian vampire tale is discussed in relation to sexuality, Irishness and the uncanny in this week’s workshop which draws on Ken Gelder, ‘Vampires and the uncanny’, in Reading the Vampire, pp. 42-64; Juliann Ulin, ‘Le Fanu’s Vampires and Ireland’s Invited Invasion’, Open Graves, Open Minds, pp. 25-55.

We also explore the figure of the female vampire as a precursor to Stoker’s Lucy and fin de siècle notions of sexual deviance in Dracula (see again Carol A. Senf, ‘Daughters of Lilith: Women Vampires in Popular Literature’, in The Blood is the Life, pp. 199-217).

For background to ‘deviant’ sexuality debates, see Elaine Showalter, ‘Decadence, Homosexuality and Feminism’, in Sexual Anarchy, pp. 169- 187; Stephen Dryden, A Short History of LGBT Rights. Carmilla’s folkloric ancestors will be identified through a comparison with the staking of Peter Plogojovitz in Calmet (week one).

Part Two: The Development of the Vampire Novel

Week 6 ‘Dialectic of Fear: Gender and Inversion in Bram Stoker’s Dracula’

Workshop text: Bram Stoker, Dracula (1897) ed. by Roger Luckhurst (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011). This week we explore the most famous vampire narrative of all in relation to theories of deviant sexuality in Christopher Craft, ‘“Kiss Me with Those Red Lips”: Gender and Inversion in Bram Stoker’s “Dracula”’, Speaking of Gender , pp. 216-42; colonisation in Stephen Arata, ‘The Occidental Tourist: Dracula and Anxiety of Reverse Colonisation’ in Bram Stoker, Dracula, ed. by Nina Auerbach and David J. Skal, pp. 462-470 . We will be thinking about why vampires don’t cast reflections and looking at the origins of the myth via a folklore and aesthetics approach in Sam George, Open Graves, Open Minds, pp. 56-78. Finally, we will gesture backwards to the vampire theatre and forwards to theatrical adaptations of Dracula taking into account Stoker’s experiences as a theatre manager (David Skal’s, ‘His Hour Upon the Stage: Theatrical Adaptations of Dracula’, in Nina Auerbach and David J. Skal, pp. 371-89).

Week 7 ‘Vampire Aesthetics: Oscar Wilde and the Artist as Vampire’

Workshop text: Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), ed. by Joseph Bristow (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006). Dorian Gray and Dracula are two of the most famous fictional characters ever conceived; here we explore vampire motifs and Wildean aesthetics in order to tease out the connections between the novels and their authors. Wilde’s novel will be read alongside Walter Pater’s description of the Mona Lisa as vampire in ‘Leonardo Da Vinci’, from The Renaissance (1873), pp. 79-80 and Oscar Wilde, ‘In defence of Dorian Gray’ and ‘The Critic as Artist’ from The Soul of Man Under Socialism, pp. 103-124, 213-243.

For background to debates around homosexuality, decadence etc., see Elaine Showalter’s, Sexual Anarchy: Gender and Culture at the Fin de Siècle, pp. 169-87. For aesthetics and vampiric motifs in Dorian Gray see Sam George, Open Graves, Open Minds, pp. 64-73. For Wilde and Dracula see Talia Schaffer, ‘A Wilde Desire Took Me: The Homoerotic History of Dracula’, in Dracula ed. by Nina Auerbach and David J. Skal, pp. 470-482.

Week 8 ‘Psychic Vampirism: Art, Decadence and Sexual Deviance’

Workshop texts: George Sylvester Viereck’s, The House of Vampire (1907) (Bibliobazaar, 2008); Mary E. Wilkins Freeman, ‘Luella Miller’. This week we investigate the psychic vampire beginning with Nina Auerbach’s ‘Vampires, Vampires’ in Our Vampires, Ourselves, pp. 102-6 Sarah Jackson, Luella Miller: Marxist Feminist Vampire Story. The novel by Viereck casts Wilde in the role of psychic vampire while art itself is the vampiric province of a master race. David Skal’s analysis of the relationship between Stoker’s Dracula and the writings and public personae of Oscar Wilde, ‘Mr Stoker’s Book of Blood’, in Hollywood Gothic, pp. 9-75 and Talia Schaffer (see Dracula) will also be useful in relation to the vampiric representation of Wilde in the novel. For a detailed analysis, see Lisa Lampert-Weissig, ‘The Vampire as Dark and Glorious Necessity in George Sylvester Viereck’s House of Vampire’ in Open Graves, Open Minds, pp. 79-95.

Part Three: New Directions: Vegetarian Vampires, Adolescents and Undead Teens

Week 9 ‘Vampire Lore in the Twentieth Century’

Workshop texts: Montague Summers, ‘The traits and Practice of Vampirism’ and ‘The vampire in literature’, in Vampires and Vampirism (1929; Mineola, NY: Dover, 2005), pp. 140-216, 271-340; Anne Rice, Interview with a Vampire (1976; London: Sphere, 2008). This week we explore the sympathetic vampire and the changes to vampire lore it represents and read the work of vampirologist Montague Summers alongside Anne Rice’s Interview with a Vampire. Summers explores the vampire as a ‘citizen of the world’, transcending temporal and geographic boundaries; Anne Rice’s New Orlean’s vampires return to Europe in search of their origins. We discuss ‘Vampires in the (Old) New World’, in Ken Gelder, Reading the Vampire, pp. 108-23 to begin with and Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s ‘Monster Theory’. Rice takes an unorthodox approach to the genre, having the vampire come out of the closet and make himself known, speaking first hand through an interview on a tape recorder. An extract from The Dracula Tapes, a 1970s retelling from the perspective of the vampire, will kick start our discussion of how the vampire gains a voice and a conscience in Rice. Damnation, morality and faith are explored via ‘Postexistentialism in the Neo Gothic Mode’, Mosaic, 25.3 (1992), 79-97. Rice’s Vampire Child’ is explored through accounts of Catholicism and the creation of Claudia (The Guardian, October, 2010).

It is useful to also catch up on the rise of undead cinema at this point. See Stacey Abbott, ‘The Undead in the Kingdom of Shadows: The Rise of the Cinematic Vampire’, in Open Graves, Open Minds,pp. 96-112 and ‘Film Adaptations: A Checklist’ in Nina Auerbach and David J. Skal, pp. 404-7.

Week 10 ‘Paranormal Romance: Sex and the Body in Buffy and Twilight’

Workshop texts: Joss Whedon, ‘Innocence’, Marti Noxon, ‘Surprise’, Marti Noxon, ‘Buffy versus Dracula’ Buffy the Vampire Slayer (season 2, episode 13 and 14; Season 5, episode 1); Stephenie Meyer, Twilight (London: Atom, 2006); extracts from Breaking Dawn (London: Atom, 2008), pp. 69-89, 376-95, 436-49; Buffy Handout [Canvas].This week we look at the appeal of paranormal romance and teenage sexuality in vampire literature. We will analyse new themes around abstinence and chasteness in relation to the vampire and explore the consummation of Edward and Bella’s relationship in Twilight, contrasting this with vampiric sex between Buffy and Angel in Joss Whedon. See Whedon’s commentary on ‘Innocence’ ; Fred Botting, ‘Romance never dies’, in Gothic Romanced, pp. 1-34, and Lucinda Dyer, ‘P Is for Paranormal–Still’ as a starting point. Pertinent approaches to sexuality and the body in Buffy and Twilight will be discussed.

See Chris Richards, ‘What Are We? Adolescence, Sex and Intimacy in Buffy the Vampire Slayer’, Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, 18 (2004), 121-37; Vivien Burr, ‘Ambiguity and Sexuality in Buffy: A Satrean Analysis’, Sexualities, 346.6 (2003); Rhonda Wilcox, ‘Every Night I Save You: Buffy, Spike, Sex and Redemption’, Why Buffy Matters, pp. 79-89; Anne Billson, ‘Love and Other Catastrophes’, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, pp. 46-61; Anna Silver, ‘Twilight is Not Good for Maidens’, Studies in the Novel, 42.1 (2010), 121-136 together with essays by Catherine Spooner, Sara Wasson and Sarah Artt (on Twilight), Malgorzata Drewniok (On Buffy)in Open Graves, Open Minds, pp. 146-164, 181-224, 131-145.

Week 11 Letting the Right One In: Teen Demon and Vampire Child

Workshop text: John Ajvide Lindqvist, Let the Right One In, trans. Sederberg (Quercus, 2009); Thomas Alfredson, Let the Right One In, 2008 [the film]. This week we investigate why vampires need to be invited in and explore the representation of the vampire child or adolescent in contemporary fiction (gesturing back to Laura in Carmilla and Claudia in Interview). Eli is 12 years old but has been a vampire for 200 years, forever frozen in childhood, and condemned to live on a diet of fresh blood. We investigate Lindqvist’s novel as the final taboo, a study in darkness, liminality and sexual deviance.

For background, see Catherine Spooner, ‘Teen Demons’ in Contemporary Gothic, pp. 87-124; ‘Other’, in Mark Currie, Difference, pp. 113-4; Margorita Georgieva, ‘Consuming the Child’s Flesh’, in The Gothic Child, pp. 116-120. For Lindqvist, see Ken Gelder, ‘Our Vampires Our Neighbours’, in New Vampire Cinema; ‘I-Vampire’ in Stacey Abbott, Undead Apocalypse, pp. 145-160; Marie Galine, ‘Nordic Wilderness: the Gothic Stance of Let the Right One In’

Week 12 ‘A Return to Folklore and Confronting Death in Young Adult Vampire Fiction’

Workshop text: Marcus Sedgwick, My Swordhand is Singing (London: Orion, 2006). We conclude by looking at the return of the East European folklorish vampire in Sedgwick’s novel and discuss his departure from the alluring romanticised creature that dominates young adult fiction elsewhere (via historicism and the folk tale). See Agnes Murgoci, ‘The Vampire in Roumania’, Folklore, 37.4, (1926), 320-349; Jan L. Perkowski, ‘The Romanian Folkloric Vampire’, East European Quarterly, 16:3 (1982), 311-322.

Marcus’s novel deals sensitively with ‘otherness’ and confronting death and we consider these themes in relation to the vampire in the context of young adult fiction. Marcus’s essay ‘The Elusive Vampire: Folklore and Fiction, Writing My Swordhand is Singing’ in the Open Graves, Open Minds, pp. 264-275 lays bare his research for the novel and we explore the importance of early folklorist accounts and theories of the folktale in relation to both the structure and content of the narrative.

See extracts from Vladimir Propp, Theory and History of Folkore (1984) and Morphology of the Folktale (1968) and James George Frazer’s The Golden Bough (1890, 1906-15).

Reading and other Resources:

Core Texts: The leading text book for this course is Sam George and Bill Hughes, eds, Open, Graves, Open Minds: Representations of Vampires and the Undead from the Enlightenment to the Present Day (MUP, 2013). A full critical reading list is posted on the module site.

Research Website: This module developed out of a major research project convened by Dr Sam George, and hosted at University of Hertfordshire. Students can sign up to the research site for the Open Graves Open Minds Project and browse the articles, resources etc. and keep up to date with recent posts, events, and other material.

Assessment: The course is assessed via a 6,000 word research project supervised by Dr Sam George. 6,000 words is exactly the right length for a journal article and students are supported in turning their project into a published piece. Students will develop their own research question in relation to the representation of the vampire in literature (and other media).

There is a rich archive of projects, dating back to 2010, which students can request for reference. Here are some examples of what previous students have written on:

‘Monstrous Bodies: Monsters that matter and the matter of monstrosity in Lindqvist’s Let the Right One In’

‘How do writers negotiate the boundaries between child and adult, innocence and experience, human and vampire in literary representations of the vampire child? Can these transgressive, liminal or taboo figures ever be redeemed?’

‘‘Daughters of Lilith: Has the female vampire become more empowered or sympathetic in the hands of female writers, or is it forever tied to its monstrous archetypes in myth and folklore?’

“I myself am of an old family, and to live in a new house would kill me’ (Count Dracula). How can phenomenology and Bachelard’s theory of the ‘poetics of space’ inform our understanding of the nineteenth-century vampire? Are there any limitations to this approach?’

‘Alterity, Assimilation and Anti-Semitism: How did the figure of the wandering Jew inform the representation of the vampire in fin-de-siècle Britain?

‘The Postvampire: How do the non-traditional representations of vampires in Octavia Butler’s Fledgling and Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire reflect the emergence and concerns of a posthuman society?’

‘Homosexual/Hypersexual Demons: How far is the vampire in nineteenth-century literature shaped by anxieties over sexual deviance?’

‘Revenants, Vourkalakas and Oupirs: How and to what end did the literary vampire abandon his folklorish (peasant) roots and leave his calling card in polite society?’

‘Capital and the Corpse: How has the 21st century world system, particularly with America as the world hegemon, dynamically effected the popular depiction of the vampire?’

‘Humanising the Vampire: A critical analysis of modern American depictions of the vampire figure and its relationship to youth culture’

‘Sight, Seeing and the Supernatural: What role did ideas around perception, sexuality and identity play in shaping the representation of the Victorian vampire?’

‘How have novels sought to negotiate difficult theological and philosophical questions regarding vampire nature, undeadness, existentialism and free will?’

To make an enquiry about this module, please email Dr Sam George: s.george@herts.ac.uk

To find about fees and admission onto the programme, please email Dr Chris Lloyd: c.lloyd@herts.ac.uk or visit the programme site MA Literature and Culture Online

For me, Reading the Vampire was the perfect module. The lecturer was so enthusiastic about the subject (it made us enthusiastic), her selection of primary and secondary texts gave us a strong sense of things from week one (but were also enjoyable reads), and this all led to an essay of our choosing that we could submit to an academic journal. I would thoroughly recommend this module. What you think you know about the vampire is probably wrong.

Brian Jukes (former student)

Pingback: Roger Luckhurst, ‘From Dracula to The Strain: Where do vampires come from?’ | Open Graves, Open Minds

Pingback: Dark Arts: UCAS student wants to study wandology at Hogwarts, how about ‘reading the vampire’ at Hertfordshire? | Open Graves, Open Minds

Is there a notification list for this?

Hi David,

We’re not sure what you mean by a notification list. Do please feel free to contact us for any further information.

Bill

Hello,

I am interested in applying for the next run of ‘Reading the Vampire’ module which I assume is in January 2022?

When will the next module dates be posted and when do applications open? Can I sign up anywhere to receive notification of dates & applications opening?

Many thanks.